(An edited version of this piece first appeared in Marwar magazine, January-February 2015 edition.)

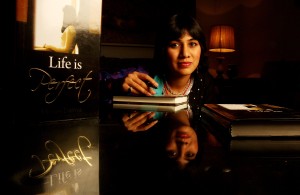

Himani Dalmia accompanying her guru Vidushi Malti Gilani on stage during a Sabrang Utsav performance in New Delhi.

‘When you are eighty years old, this gift will stand by you,’ my guru says to me often. Her silver hair falls in wisps around her face, held back in a small, determined bun. Her face is still striking, even with its deep lines and folds. Her beauty would have been no ordinary thing in her youth. ‘I have seen so many people who lose interest in life, who sulk in their rooms, waiting for their children and grandchildren to dutifully take out time for them. When all the trappings and bustle of youth are gone, your music will give your life richness.’

I have no doubt in her prophecy. If there could ever be a role model for aging gracefully, it would be my Hindustani shastriya sangeet guru, Vidushi Malti Gilani. It has been twenty years now since my first music lesson with her. I was ten years old at the time, sitting obediently by my mother in my shorts and t-shirt. She was my third guru and, to my pre-teen eyes, appeared the most forbidding yet. My first teacher had been a kurta-pajama clad gentleman in his thirties, who prolifically taught me enough bandishes to fill up three notebooks in three years. He would play the harmonium rather sleepily as I sang along. My mother often sat with me in those lessons to prevent his nodding off completely but I hardly blame him for his somnolence. One cannot teach a six, seven or eight-year-old anything more than the words and melodies of songs, which, for a classical musician, is like laying out ingredients repeatedly in a cooking class without doing any actual cooking. My second teacher tried to take my cousins and me to the next level. My lessons with her were shared with my tau’s daughter, Katyayani, who is one year older than me. We would be carted off in a car, reading Nancy Drew, Paula Danziger or Judy Blume books on the way. Our new teacher was an affectionate and charming lady who introduced us to the taanpura and the tabla for the first time. After exposing us, however, she preferred to use practical ‘petis’, or electronic boxes that simulated the sound of these instruments, for lessons. She taught us a plethora of classical and semi-classical songs. Our repertoire expanded considerably but we were not able to continue our lessons with her for more than a year because her own professional music career took off at lightning speed. She felt she would not be able to do our lessons justice and bowed out of our lives. Today, she is one of the best-known musicians in the country: Shubha Mudgal.

My mother now began the quest for a new guru and found Vidushi Malti Gilani, one of the senior-most disciples of the legendary twentieth century maestro and doyen of the Patiala Kasur gharana, Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan. Malti aunty, as I called her then, was a regal, serious and impressive person, always dressed stunningly in a kanjeevaram sari, a string of pearls and kundan earrings, with a signature red bindi drawn in by hand. She wore arresting red-frame spectacles and, on occasion, Versace and Prada sunglasses of outlandish designs. Malti di, as I call her now, was always friendly and loving but, from the very beginning, had a different approach to my musical education from my previous teachers. Maybe it was because I was finally old enough or perhaps because that was the only way Malti di could teach but the way I understood music was entirely deconstructed by her. She started with Raga Yaman, a standard beginning for a shastriya sangeet student. Malti di was a purist and did not believe in electronic instruments. She spent the first twenty minutes of every class tuning the taanpuras and teaching me how to tame these wilful instruments. She had a tabla player present for every lesson, some less-than-satisfactory ones in my early years and later a senior musician, Ustad Nawab Ali, who became an integral part of my musical training.

Lessons with Malti di were detailed and thorough from the beginning. No simple melodies for her. From my very first class, she set about introducing me to the concept of taal. I would spend entire lessons just reciting dha dhin dhin dha while one of the less-than-satisfactory tabla players, alternately drowsy and flattered, rapped away at his instrument. After that, entire lessons singing a single line. Soon, Malti di introduced me to taans. Entire lessons comprising one taan repeated countless times until it rolled off my tongue and wrapped itself into the taal. And the ragas began to stack up – Bhupali, Kedara, Kamod, Bageshari, Rageshari, Bihaag, Malhaars, Bahaars, to name a smattering.

As I entered my teens, I took responsibility for my music. It graduated from being something my mother aligned for me into something that was so intricately linked with my life and who I was that the number of lessons and time spent there was no longer in question. I was clear, of course, that music would never be a career for me. Academics and school life held precedence over music then, just as my work in business does today. It was in my teens that I learnt to compartmentalize my life. My “worldly” life led me from being an academic achiever at Sardar Patel Vidyalaya to a literature student at St Stephen’s College and Oxford University to writing for the Edit Page of the Times of India to publishing a novel and, finally, to committing myself to a life in business, working in my father VN Dalmia’s fast-growing foods company. Literature and writing was my first love but even that took a back seat to my professional career. Music was yet another parallel life. I went for lessons four, sometimes five, times a week through my school and college days. Even while I worked at the Times of India, I took special permission to leave early so that I could pursue my music. One of my biggest concerns before joining the work force full time was what would happen to my music. But my parents had brought me up with my mother’s strong middle class values, as an absolute antidote to the privileged environment I was born into. There was no question of taking my time or dabbling about in the arts. Literature and music could hone my mind and give me intellectual stimulation but, at the end of the day, I needed to pull my own weight. As far as my parents were concerned, what career I built was up to me, as long as I didn’t depend on dole-outs from them or any future inheritance for my subsistence. So, I committed to office hours and music got entrusted to the weekends. I worked towards building India’s first olive oil and canola oil brands, Leonardo and Hudson respectively, by day, moonlighted as a writer by night and continued music as an intellectual and spiritual pursuit in what time remained.

It took me a while to reconcile myself to this compartmentalization; to accept that business, writing and music could all co-exist, that I did not have to give one of them up. It always seemed disorderly, causing me to be momentarily stumped when asked the ubiquitous opening question at social gatherings: “what do you do?”

Actually, when viewed in the light of my family history, my inclinations become far from disorderly, if not entirely natural. My grandfather, Ramkrishna Dalmia, was one of the pioneering industrialists of modern India and the name ‘Dalmia’ is almost synonymous with enterprise and business. The reality is though that, today, my family consists almost entirely of writers, artistes and academics. One of my father’s sisters was a writer whose partner was India’s then leading poet, S.H. Vatsyayan; another is a professor of Philosophy; yet another, a former professor at the Universities of Yale and Berkeley, is internationally renowned in the field of South Asian Studies; and a fourth is a pre-eminent art historian with many books to her credit. As the male heirs, my father and his brother were never presented the option of drifting into academia. Businessmen they became, yes, but they also wrote on the side. And whom did they marry? One, an academic who is today a Commonwealth prize-winning novelist and, the second – my mother – a lawyer and educationist. My own generation is populated by mathematicians, anthropologists, musicians, art historians, writers and philosophers.

These cultural leanings clearly stemmed from my grandmother, Saraswati Dalmia, a Hindi poet and Sanskrit scholar. My grandfather married her when he was already at the pinnacle of business success with a small-town woman as his spouse. Making pots of money had not compensated for his humble upbringing and he was not prepared for high society. Moreover, he had a questioning mind. The later wives he chose brought cultural refinement with them. My grandmother had studied Sanskrit, was highly educated and wrote prolifically. His next wife brought with her the culture of Lahore, then known as the Paris of the east. His last wife was a writer who went on to become well known in the Hindi literary circuit and win national awards.

It is the women, after all, that bring up the children. The offspring of Ramkrishna Dalmia from his later wives were born to double messages: one, to join the family business; and two, to value culture and creative expression. The cultural influence was too strong for his children to escape and was compounded manifold by the arrival of their own spouses.

My mother, born Nilanjana Varma, grew up in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh in a family that was proud of its ‘Kayastha’ heritage. The word ‘Kayastha’ means ‘scribe’ in Sanskrit and the patron deity of this community is the son of Lord Brahma, Chitragupta, whose job it is to keep meticulous records of all human actions as a sort of celestial journalist. The Kayastha community has traditionally been associated with education, the arts, law and administration. My mother’s family always placed a premium on education and the classical arts. In the first half of the twentieth century, they were amongst the few Indians that went to England for higher education and then occupied important posts in India’s British government. Despite a westernized upbringing, the Indian classical arts held an elevated status for them. She tells me that, in her family, Hindustani shastriya sangeet was considered the mother of all music, including western classical. Her father played the flute and the tabla, her mother sang. The families of both her parents were chock-full of accomplished musicians. The leading artistes of the day would be in and out of her family homes, where concerts were held regularly. Ustad Bismillah Khan, the twentieth century shehnai maestro, played at her parents’ wedding in Benares. Learning classical music and dance was an integral part of any Varma or Srivastava child’s education. It was never meant to be a professional pursuit but more a way of life, an added dimension to a well-rounded and wholesome personality, a sign of good breeding. My mother implemented these parenting values with her children as well – more strictly with me, her first child, and more leniently with my brother Pranav, who nevertheless took to the piano and is today an accomplished pianist with a large-scale, public solo concert under his belt.

With such strong influences of business and the arts, it seems that my fate was sealed. It’s a balancing act, for sure, but I cannot live without one or the other and the contradictions bother me no more. The reconciliation becomes easier for me since my husband is a fellow creative spirit who went from a life in the liberal arts, theatre and the media to an MBA and a corporate career. My mother-in-law too is a literary person, an art aficionado and a rasik who frequents the concert halls of Delhi, in addition to nurturing a successful and demanding professional career in education.

Himani and Akash opted for a Hindustani classical music recital by Ustad Raza Ali Khan, the current khalifa of the Patiala-Kasur gharana, at home for their wedding Sangeet.

‘You are so lucky,’ Malti di often says to me. ‘You don’t need to sing for money. You don’t need to learn quickly and put together performances and sing what sells. You can learn the true art. Our kind of music is a sadhana, a spiritual practice. I too am fortunate that I can teach you the truth behind it.’

Malti di is the founder of the Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Yaadgar Sabha, a trust founded in 1968 in memory of the great maestro. It is a unique trust because it aims to provide medical aid to musicians, the majority of whom have no medical insurance, job security or regular income. The Sabha organizes an annual concert in Delhi in the Fall called ‘the Sabrang Utsav’, after Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Sahib’s pen name. Although she is the grand dame of Delhi’s music circles, seated in the front row of almost every concert held in the city, Malti di treats these audiences to very few performances. After extensive training by both Ustad Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Sahib and his son, Ustad Munawar Ali Khan, Malti di gave numerous performances in India and abroad the 1970s and ‘80s. Thereafter, she decided to take a step back, focus on her riyaz and on passing on her guru’s gaiki to her students. The Sabrang Utsav is now one of the rare occasions that music lovers get to hear her magnificent full-throated investigation of the Patiala Kasur gharana style.

My memories of the Sabrang Utsav go back to the very beginning of my association with Malti di. At that time, Malti di would have my cousin Maya and another older student, Mala, accompany her in her performances, playing the taanpura behind her and giving vocal support. I would attend the concert with my parents, often falling asleep with my head on my father’s arm. I could not fathom the kind of music that was being performed – the gradual explorations of a raga, the layakari, the behlavas. It was all very slow and dull for me. Then, over time, as my own musical understanding grew, I would find myself in the same place at the same time of year, in a completely different state-of-mind. I began to enjoy all the performances immensely and particularly Malti di’s because I never heard her sing from A to Z in a lesson. I began to understand where she was trying to take me in my own education. As I grew, both physically and intellectually, the same auditorium and the same stage began to look smaller to me every year.

That was until Malti di decided it was my turn to accompany her on stage. I must have been fourteen or fifteen years old. My cousin Maya had left for the United States for her PHD in Mathematics and Mala was no longer taking lessons from Malti di. My cousins Amba, Katyayani and I were the senior-most students left. So, for a few years, either Amba and I or Katyayani and I were the two accompanists for Malti di’s performances. In the first few years, it was terrifying. Singing the asthayi and antara with her just to give vocal support was not a problem but Malti di would often flick her head towards us during the gaps in her singing, expecting us to throw out a few taans or behlavas. At that moment, all musical knowledge would flee my mind and I would be dumbstruck. It would take superhuman strength to tune into the sound of the tabla, understand where in the cycle of ek taal or teen taal or jhumra I was in and launch into a taan, landing correctly on sama with so much relief that I could barely complete the phrase!

I gained confidence slowly. Malti di coaxed me into doing a couple of solo performances. The Utsav was held in September every year, with preparations beginning a few months before. It was in the lead-up to the Utsav that I would feel the strain of juggling so many parallel lives. Musical fruition that needed hours of riyaz everyday could not be conjured up in convenient doses. In the month of September, music would become my number one priority. I would try to fit in as much riyaz as possible, often asking Nawab Ali Khan Sahib to come to my house for some practice with the tabla, un-supported by Malti di. And then, the big day would arrive.

Entering the auditorium itself represented a shift in the space-time continuum for me. The floral arrangements on the stage were familiar; a large print of MF Husain’s portrait of Bade Ghulam Ali Khan Sahib stood regally to one side; audience members who had arrived early murmured softly in the background, against the portentous sound of instruments being tuned. My parallel lives melted away. Now, it was just me, my taanpura, Malti di and the raga before me.

When the performance ended, when I set my taanpura down, folded my hands to the audience and departed the stage, I would be washed by a jumble of feelings – relief, gratitude, pride and self-doubt.

Life would revert to normal after the Sabrang Utsav was over. I would return to my regular schedule of music lessons over the weekends.

Now, almost twenty years after I first came under Malti di’s care, the upscale colony where her home is situated is a different world altogether. Originally occupied by old business families or defense personnel, it is now peppered with expats and diplomats. The rents have sky-rocketed and old buildings have been broken down to create modern low-rise apartment complexes. But Malti di’s home remains a safe haven.

Nawab Ali Khan Sahib and I set up in Malti di’s room, looking out at her beloved gulmohar tree. Lessons are sometimes about reviving khayals learnt years ago, sometimes about arduous voice culture and sometimes about perfecting concepts of laya. They are also sometimes about gossiping over chai, Malti di’s trips down memory lane and spending time with my cousins and her as a family. And from time to time, they are about my cousin Amba, who we lost in a car crash when I was seventeen. Although Amba and I grew up playing together, our primary interaction in her last few years was at music classes. It is at music classes and Sabrang Utsav that I miss her most.

‘Don’t let life upset you,’ Malti di says often. ‘Khan Sahib used to say: why stress or mope about things. In the time it takes to do that, you can do riyaz of several taans!’ Like any spiritual practice, my musical training is not just about notes and beat and melodies. Life lessons and anecdotes are an integral part of it, while my relationship with my guru is an overriding part of it. It is possible that, with anyone else, I would have labeled my music an unnecessary self-indulgence and given up on the battle years ago. My relationship with Malti di is much more than that of teacher and student. The path she has set me on is greater than just that of mastering a skill. It is a sadhana, a commitment to my intellect and my spirit. It gives me moments to breathe in an otherwise hectic life. It gives me a chance to tap into my multiple family legacies. Like a khayal, intricately tied to the rules of its raga and the taal it is set in, and yet ultimately unstructured and improvisatory, my life in music and with Malti di grounds me by making me a tiny member of a limitless universe and by making me struggle to achieve every success, and yet finally sets me free.